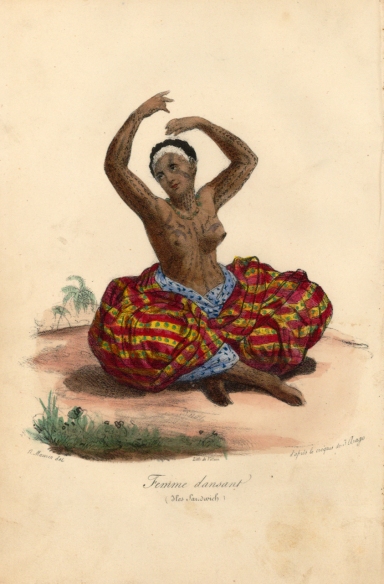

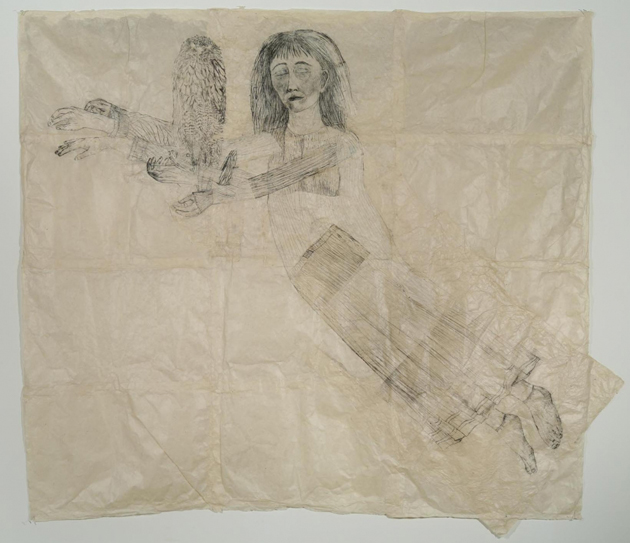

William Chillingworthʻs book, ʻIo Lani, The Hawaiian Hawk, was published in 2014, and this winter won an award for the best photography book of the year from the association of Hawaiian book publishers. Williamʻs maternal ancestors were birdcatchers in the district of Kamaeʻe, north of Hilo on the Big Island. The feathers of certain birds, many of which subsequently became extinct, were used to make the ravishing red, yellow, green, and black capes worn by the chiefs, as well as helmets, leis worn on the head and around the neck, effigies of gods, and the royal staffs known as kahili. The now-extinct mamo, pictured below, was perhaps the most highly prized of all the birds, perhaps because they were particularly difficult to catch. Found only on the island of Hawaiʻi, they were first recorded by Captain Clerke of Cookʻs third voyage in 1779. Their few yellow feathers were more vivid than those of other birds. A cape belonging to King Kamehameha I, which is now in the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, was made of 450,00 feathers, 80,000 of which were mamo feathers. As their population diminished, there was a kapu on the birds, but by the turn of the last century, the mamo had been hunted out of existence.

The following is from an essay by the Hawaiian cultural anthropologist Nathan Napoka of Maui, written for W.ʻs book. This quote from the historian Kepelino (1859) describes the different ways to catch a Hawaiian hawk, or ʻio, whose feathers were not commonly used in decoration or clothing:

There are two methods of catching the ʻio. The first involved the use of a hapapa, a long stick with a shorter stick tied to it in the form of a cross. The catcher would tie a small live bird or a captive ʻio just below the intersection of the sticks. This bait, along with the skilled ʻio call of the bird catcher, summoned the ʻio from its lofty heights. “They…hurry like human beings to save the one who is in distress. Because the Io is a bird who loves its fellow Io when in distress of when taken captive. If a live Io is tied with a cord, it struggles and jerks to and fro and cries ʻfiro.ʻ The others hear the cry of the Io that is tied up; they fly hither to rescue him. If the cord is not well tied, the captive Io will escape with the aid of its rescuers. If a man is careless or foolish he will be badly injured by the Io, as it is a bird that flies into a rage when a man comes too close. Therefore, in order to kill an Io, he should run up with a stick in hand as soon as it swoops down upon the birds tied to the hapapa and thrust it in front of the Io. It will grasp the stick with its talons, then the bird catcher twists the stick around rapidly, thus breaking its legs. And so on.

The Hawaiian hawk (Buteo solitarius), which closely resembles the Swainsonʻs hawk and the short-tailed hawk (Buteo brachyurus) found in South America, arrived in the Islands tens of thousands of years ago, presumably blown off course during its annual migration south along the coast of what would one day be California and Mexico. In order to reach the southeastern-most islands in the Hawaiian archipelago, the lost birds would have had to fly for seven or eight days before at last reaching landfall.

The biologist John Culliney writes:

Having established itself across the main islands of Hawaiʻi…before the arrival of human beings, the adaptable ʻio weathered the onslaught of environmental change that began with the expansion of the early Hawaiians [in the ninth century A.D.]. Within a few centuries, lowland forests were greatly altered and diminished as growing human populations burned wide areas for…agriculture. Many bird species became extinct, replaced by new kinds of prey that arrived with the Polynesian canoes…For a time, ʻio populations thrived in the increasingly turbulent ecological disruption brought by the human pioneers, and the Hawaiians took significant notice of these fierce birds that soared with such a powerful presence on the trade winds.

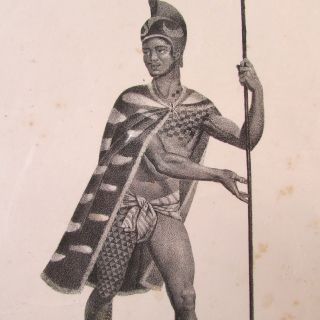

With the establishment of the Hawaiian kingdom in the late eighteenth century and the rise of the Kamehameha dynasty, the ʻio became the bird of kings; a royal totem of enormous power and majesty.

The high priest of the sacred ʻIo cult lived in the valley in North Kohala where Kamehameha I was first hidden as a child from the rivalrous chiefs who wished to kill him. One of the high priestʻs descendants, Montano, remembered that “the priesthood of Iolani was the highest priesthood of the islands…Neither chieftains nor priests dared utter the word Io…Io is the Holy Spirit, the invisible someone. There was no human sacrifice on this altar…The people by this religious order did believe, however, in stoning a wrongdoer to death. The priests of Io were feared and respected…Io to us is Jehovah to other peoples.”

The ʻio was once on the list of endangered species — they are killed by hunters, poison, dogs, cats, the mongoose, starvation, and the mysterious, at least to me, “actions of introduced ungulates” — but is no longer considered a threatened bird. They are raucous during the breeding season in the spring, when they make a piercing cry, much like their name in Hawaiian. They customarily have a clutch (such a good word) of one egg. Should you be on the watch for an ʻio, mature birds have yellow legs, while the legs of juveniles are fittingly greenish. (An ungulate is a large mammal who may be classified as odd-toed, that is, horses and rhinos, or even-toed, such as cattle, pigs, giraffes, and camels, the latter two yet to be seen in the Islands, at least outside the melancholy zoo in Honolulu.)

In a survey made by the United States government in 2007, there were perhaps three thousand ʻio living on the Big Island, primarily in the district of Kohala, with a range of 2,372 square miles (58% of the island).There have been occasional sightings of the bird over the last thirty years on Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, and Maui.