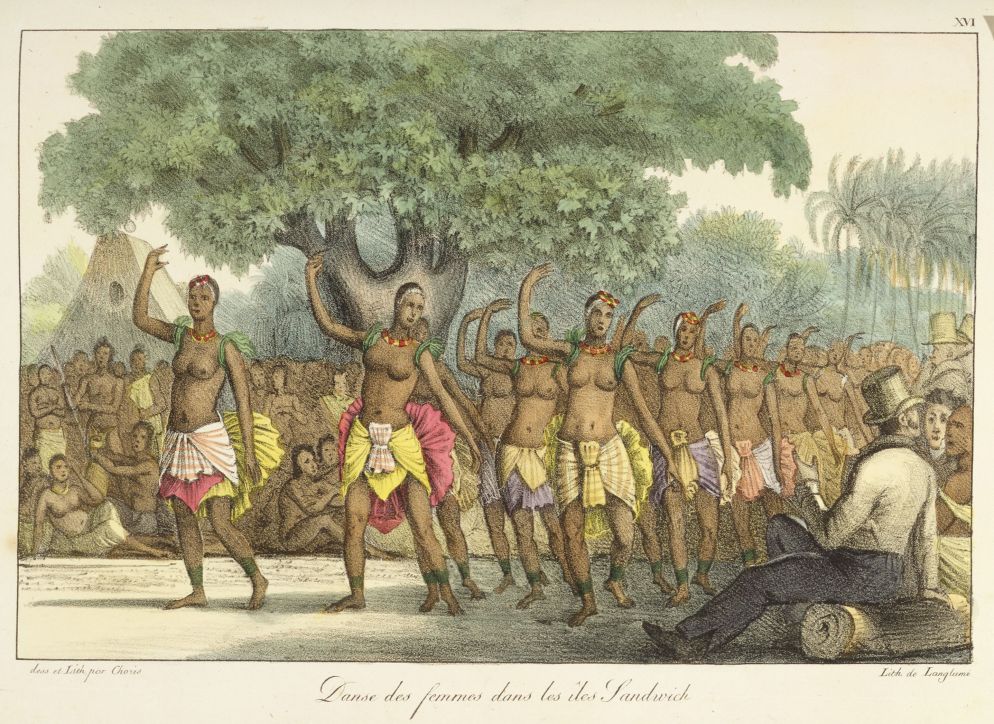

In the spring of 1820, the high chief of Kona, Kuakini, a younger brother of the late king’s powerful widow, Ka’ahumanu, was the first person of important to greet the Congregationalist missionaries upon their unexpected arrival in the Islands. He was very tall and very big, and wore a traditional malo or loincloth with a short cloak, known as a kihei, thrown around his huge shoulders. He invited the foreigners to his house, but they refused his invitation. Thomas Hopu, a young Hawaiian convert to Christianity who had sailed with the missionaries from New England, was surprised by the rudeness of the Americans and advised them to reconsider. They reluctantly agreed to attend a feast given by Kuakini, who was notorious even among the generous Hawaiians for his extravagance. Kuakini had earlier written to the president of the United States in the hope of exchanging names with him, as was a traditional Polynesian custom, and although President Adams did not deign to answer, Kuakini had begun to refer to himself as John Adams (according to the historian Kamakau, Kuakini was also a notorious patron of thieves, keeping men solely to plunder ships and the stores of foreign merchants). Although there was ample and varied food at the feast, the missionaries would not eat the food. Kuakini even had wine for them, which they declined, taking only sips of coconut water. He was an accomplished dancer and kept the finest troupe of dancers in the kingdom, but the missionaries ignored his invitation to watch the dance. The Reverend Hiram Bingham, the leader of the mission, and Asa Thurston left the feast early, announcing that in future they only wished to meet with the king.

With Hopu serving as intermediary and with the help of John Young, the late Kamehameha’s English counselor and friend, the two men at last met the young king, Liholiho. They arrived while he was eating dinner with his five wives, two of whom were his sisters, and one of whom had been married to his father. Refusing to be seated, the missionaries read aloud formal letters from the Board in Boston. One can imagine — or perhaps not — the reaction of the king and his queens to the dry and somewhat naïve instructions of the Board. A private Missionary Album with confidential advice for the First Company, which was not read aloud, contains surprisingly benign, although ultimately ineffective instructions, particularly concerning involvement in the kingdom’s politics:

Your views are to be limited to the low, narrow scale, but you are to open your hearts wide and set your goals high. You are to aim at nothing short of covering these islands with fruitful fields, and pleasant dwellings and schools and churches, and of raising up the whole people to an elevated state of Christian civilization. You are to obtain an adequate language of the people; to make them acquainted with letters, to give them the Bible, with skill to read it…to introduce and get into extended operation and influence among them, the arts and institutions and usages of civilized life and society; and you are to abstain from all interference with local and political interests of the people and to inculcate the duties of justice, moderation, forbearance, truth and universal kindness. Do all in your power to make men of every class good, wise and happy.

Out of fear of Queen Ka’ahumanu, or perhaps an instinctive foreboding, Liholiho refused to give the missionaries permission to land in the Islands. Although his father, Kamehameha I, had asked the English captain and explorer, George Vancouver, to send religious instructors to the Islands when Vancouver returned to England, it had been in the interest of increasing the wealth of his kingdom, not his chances of salvation. Liholiho told Bingham that Ka’ahumanu was away fishing, and he could not make a decision without her. Lucy Thurston wrote in her journal that the missionaries then invited the king and his family to dinner on the Thaddeus. The king came to the ship in a double canoe of twenty paddlers and a large number of attendants. Although Westerns had been present in the Islands for many years, they had been men — ships’ captains, sailors, escaped convicts from Australia, whalers, merchants, and adventurers.

The king was introduced to the first white women, and they to the first king, that each had ever seen. His dress on the occasion was a girdle, a green silk scarf put on under the left arm, brought up and knotted over the right shoulder, a chain of gold around his neck and over his chest, and a wreath of yellow flowers upon his head. The next day several of the brothers and sisters of the Mission went ashore, hoping that social intercourse might give weight to the scale that was then poising (sic). They visited the palace. Ten or fifteen armed soldiers stood without, and although it was ten or eleven o’clock in the forenoon, we found him on whom devolved the government of a nation, three or four of his chiefs, and five or six of his attendants, prostrate on their mats, wrapped in deep slumbers.

Hiram Bingham was shocked that Liholiho wore no shoes, stockings, pants, or gloves, although Thomas Hopu had warned the chiefs and chiefesses to dress with care when they called on the missionaries. As the aliʻi were accustomed to wearing Western clothes (merchants had long supplied them with suits, and bolts of Indian and Chinese textiles for gowns), most of them obligingly appeared for their daily visits in gowns of Peking silk and striped taffeta, brocade jackets, and heavy velvet waistcoats, which were stifling in the heat. Some of the ali’i, hoping to please the haoles, evoked instead their private ridicule by their odd assortment of clothes — one of many melancholy ironies that was to ensure they remained unknown to one another. In his memoir, the missionary Charles Stewart described a “monstrously large” chiefess dressed in white muslin, “thick woodsman’s shoes, and no stockings, a heavy silver-headed cane in her hand, and an immense French chapeau on her head!”

The royal women and their chiefs and attendants arrived at the ship each morning, seated under red and gold Chinese umbrellas on the platforms of large double canoes as they were fanned by a dozen men. The redoubtable Hiram Bingham was impressed by the agility and physical grace of the paddlers, if little else:

Ten athletic men in each of the coupled canoes making regular, rapid, and effective strokes, all on one side for a while then, changing at a signal in exact time, all on the other. Each raising his head erect and lifting one hand high to throw the paddle forward…dipping their blades and bowing simultaneously…making the brine boil and giving great speed to their novel seacraft. These grandees and their ambitious rowers gave us a pleasing indication of the physical capacity, at least, of the people whom we were desirous to enlighten.

The missionary wives sewed a dress for the queen mother, Keōpūolani, that so delighted her that she ordered more for her attendants and herself, waiting as the foreign women, unused to the dry heat of Kona, dazedly cut and stitched her a wardrobe. The chiefesses and queens were particularly taken with the Chamberlain’s young daughter and decided to adopt her, or hana’i, a practice common in Hawaiian families. To their surprise, the Chamberlains refused, but reluctantly agreed to let the child be taken ashore for the night, a gesture that helped to convince the queens that the missionaries meant them no harm. Lucia Holman, the prettiest of the missionary wives, wrote that one of the queens, “got me into her lap, and felt me from head to foot and said I must cow-cow and be nooe-nooe, i.e., I must eat and grow larger.” When Lucia walked with Nancy Ruggles and Maria Loomis on shore, the delighted Hawaiians surrounded them, touching and poking them with curiosity.

Over the next weeks, the missionaries waited patiently for the king’s decision, confident of the sanctity of their mission (to their irritation, the chiefs were easily distracted, at one point by a troupe of musicians), as they made excursions on shore, sailed aimlessly up and down the coast on the Thaddeus, and visited with the Hawaiians. As the moon rose one evening, Asa Thurston and Hiram Bingham climbed to the maintop of the Thaddeus, and while their wives, the captain and crew, and the ali’i of Hawai’i Island watched in silence, loudly shouted the hymn they had sung at their ordainment in New England and again at Park Street Church when they left Boston for the distant Sandwich Islands:

Head of the Church Triumphant,

we adore Thee,

Till thou appear,

The members here,

Shall sing like those in glory:

We lift our hearts and voices,

In blest anticipation,

And cry aloud,

And give to God

The praise of our salvation.

So much of our written Hawaiian history from the western perspective is written in journal form, or in letters, or accounts in publications. These venues are often stilted and chronological. What a joy to read Susanna’s compilation of all these into a story into which we can place ourselves. watching these two cultures slide awkwardly into each other. Thanks.

LikeLike

Mahalo, ditto Toni, I enjoyed this edition quite a lot.

LikeLike